My July 2020 visit to MCA Denver wasn’t the first time in two years of art-browsing in the Mile High City that I felt, wow, I am seeing important work, and I’m not even in NYC or LA. This local institution has reliably shown it can “bring it,” with blockbuster shows such as “Francesca Woodman: Portrait of a Reputation” and “Tara Donovan: Fieldwork,” both of which I had the pleasure of reviewing for publications.

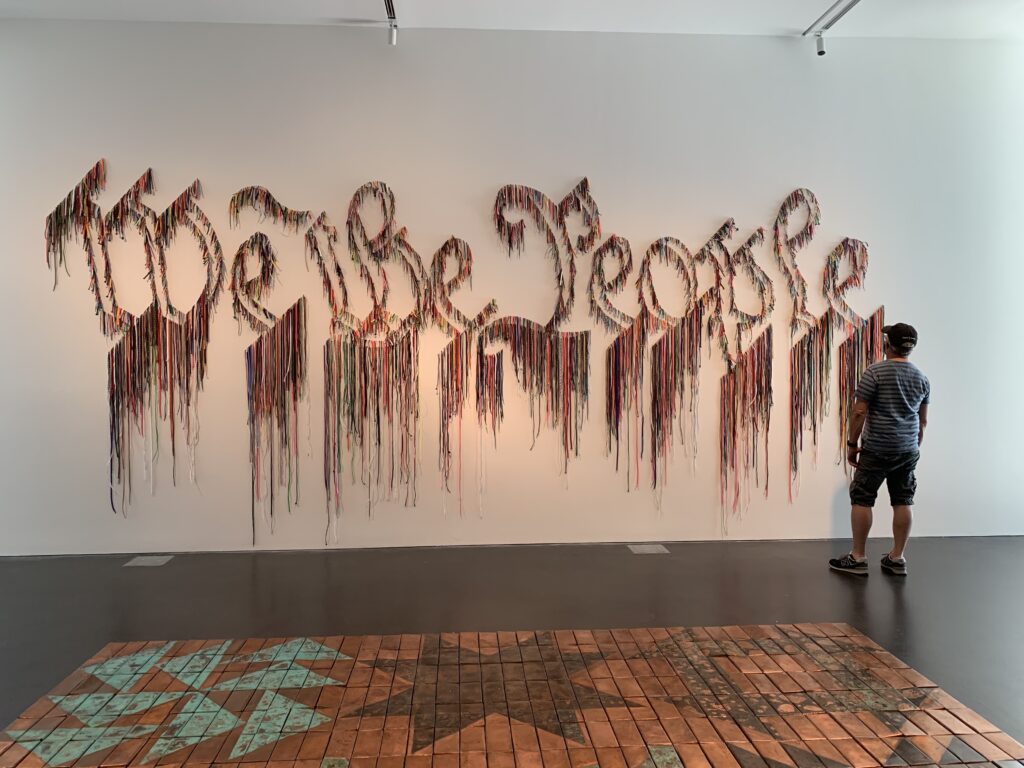

That feeling of art-viewer gratitude swelled in me again with “Nari Ward: We the People,” a tremendous journey into empathy, hope and human potential, even though the implied subjects are sobering: the suffering of marginalized communities, the legacy of slavery, the tenuous state of our democracy, and humanity’s many overlooked narratives, to name a few. You see, I chose to find optimistic meanings in Ward’s installations and wall pieces, rather than hopelessness over society’s stagnation when it comes to Constitutional promises of equality and justice. The messages might dovetail all too poignantly with the justified outrage from Black Lives Matter protesters, but Ward’s work is not necessarily designed to evoke anger. The takeaways are up to the individual viewer. And I chose to let the messages be potential instigators for change.

Ward lives and works in Harlem, in a studio that was once a firehouse, allowing him plenty of room to collect the multitude of found objects that come together for his installations. “We the People” brings together many of the works that Ward has become famous for over the last three decades, including “Amazing Grace” (1993), a gallery-size installation with sound. Ward collected dozens of well-worn baby strollers, and with each iteration at various venues, the strollers are arranged around knotted and flat fire hoses. Mahalia Jackson’s “Amazing Grace” plays in the background, lending a plaintive element. One interpretation is that the shape evokes a slave ship. In an interview with curator Gary Carrion-Murayari, Ward says he would like to think the baby carriages represent emergence and potentiality.

Probably the most resonant and timely installation from my point of view is “Father and Sons” (2010), a four-minute video using close-ups and long shots to show a retired police officer coaching his sons on reciting their Miranda rights. The details of the images and the compulsion to read the subjects’ emotions make the work quite mesmerizing, and more so in the context of black youths’ fraught relationship to law enforcement.

Here’s a sampling of other pieces in this powerful show:

You might not agree with my takeaways from “We the People,” and even find them too Pollyannaish. That’s why you need to see the show for yourself (through Sept. 20, by reservation). Viewing the many photos in this post really isn’t the same as being immersed in the art and absorbing the museum’s thoughtful curation. We — yes — we the people, should be Black Lives Matter allies. Art is one way to make that happen.